7 artists shaping new Ukrainian anti-colonial art

a curated list by a guest contributor Valeria Radkevych.

Russian Colonialism 101 is the first newsletter to shed light on Russian colonialism. It is part of the Volya Hub network, expanding global awareness of Russian colonialism.

hihi everyone,

Maksym is here. Art is the best shortcut for understanding Russian colonial nature and Ukrainian anti-colonial resistance. For the new edition of my RC101 collab series, I’ve invited an amazing guest contributor to offer you a quick entry tour into the breathtaking world of the new wave of Ukrainian art that is synonymous with anti-colonial resistance. Learn and enjoy.

A common opinion paints art and culture as soft power that subtly influences societies. I disagree. Judging from my own experience as a Ukrainian living next to an abusive empire, art and culture can be easily weaponized by empires and dictatorships but might also become a powerful outlet for anti-colonial resistance.

Art can be direct and visceral; it may be loved or hated. But when it comes from the place of free will and struggle for freedom, it tells the truth that is hard to ignore.

My name is Valeria Radkevych. I am a Ukrainian art critic and researcher with an MA in Visual Arts from the University of Bologna and Paris 1—Pantheon Sorbonne. Initially from Luhansk, I lost my home to the Russian imperial invasion in 2014. Since then, I’ve witnessed Moscow trying to eradicate our identity and culture and erase another generation of brilliant Ukrainian artists.

That’s why I became so fascinated with art, which defies the role of a mere decoration or a pleasant image but stands as an uncompromising testimonial of reality.

Recently, I launched my own blog, A Quiet Catalyst. It is a curatorial project that highlights Ukrainian artists who refuse to be silenced and who use their skills and practice to forge resilience. You can also follow me on Substack.

For this edition, I would love to share with the audience of Russian Colonialism 101 my personally curated selection of anti-colonial voices from the breathtaking contemporary art world of wartime Ukraine. It is based on my recent blog essay that looks into the ways Ukrainian art has been responding to Russian colonisation. Please check it out.

Art is not separated from politics; it IS politics. Remember that.

Alevtina Kakhidze

Alevtina Kakhidze is a Ukrainian multidisciplinary artist, performer, and educator. She scrutinises situations and narratives, applying a logic that is nearly engineering. Deconstructing ideas, she creates artwork that often resembles an infographic. She wants messages to arrive loud and clear, making much of her art self-explanatory.

In her work, Cancel Russian Culture is Medicine (2022), Kakhidze highlights the multiple spheres of Russian influence on a global scale. She reflects on what exactly makes Russia so influential. Is its economy built on international trade? Is it an invasive propagandistic religion? Its culture? Media? Thus, these creatures tend to possess multiple heads, hands, and tentacles that reach out to deceive and destroy. The two-headed eagle on the Russian coat of arms is another rather schizophrenic symbol that gives art plenty of space for interpretation.

Kateryna Lysovenko

Kateryna Lysovenko’s practice takes the viewer back to the mythological dimension, where legend, metaphor, and fusion of human and non-human are central to the narrative. These two artworks relate to a crucial colonising step: creating an imperial cultural institution, like a museum, where the knowledge can be organised according to the coloniser’s worldview. The Louvre and the British Museum are good examples of such institutions. However, while the colonial past of both France and Great Britain has been an ongoing discussion for decades, Russia remains on the list of active colonisers. So does The Hermitage. Both the drawing and the installation depict the actual objects that belong to the cultures of the colonised nations, and that Russians stole and stored in the Russian museum’s collection. They are united in a circle, a sort of “group therapy session,” in a silent debate on their provenance and histories.

Zhanna Kadyrova

Zhanna Kadyrova is one of the most internationally acclaimed Ukrainian contemporary artists. Strictly speaking, her work has never been apolitical. The very process of art-making is a way of providing critical commentary, whether it is corruption, the state-of-the-art market, or war. Since the beginning of the genocide in Ukraine in 2022, Kadyrova paused all the projects that did not directly speak of war, helping her raise funds for the Ukrainian military—a common practice among Ukrainian artists, writers, and musicians these days. Instrument (as captured in the videos above) is one of her latest installations. It is a functioning organ, its tubes ending with exploded Russian shells. The artwork is open to interpretation, one of them being the way Russia weaponises its art and culture, simultaneously absorbing the cultures of the territories it occupies.

Nikita Kadan

Nikita Kadan was one of the first Ukrainian artists to begin putting the Soviet legacy and contemporary Russia into a colonial perspective while enjoying international recognition. The Possessed Can Witness in Court is a group of objects displayed in what could be a museum installation. A few of them are made by the artist himself, like the neon sagoma of the Crimean peninsula he created in 2014 after Russia invaded and annexed this Ukrainian region. Other things that populate these shelves come from the collection of the National Museum of History of Ukraine, authors of most of them unknown. The living plant here is a symbol of care: these objects are not abandoned, someone keeps an eye on them, dusting and moving them around from time to time. The displayed objects all relate to the history of Donbas and Crimea, Ukrainian regions occupied by Russia in 2014. The list of objects is present, but it hardly explains their purpose. In fact, taken out of the imperial context of the Soviet Union, they either remain empty shells (some of quite dubious artistic quality) or acquire a new meaning provided by the beholder.

But most of all, this collection gives an idea of how hollow and meaningless imperial propaganda becomes when nobody is there to narrate it.

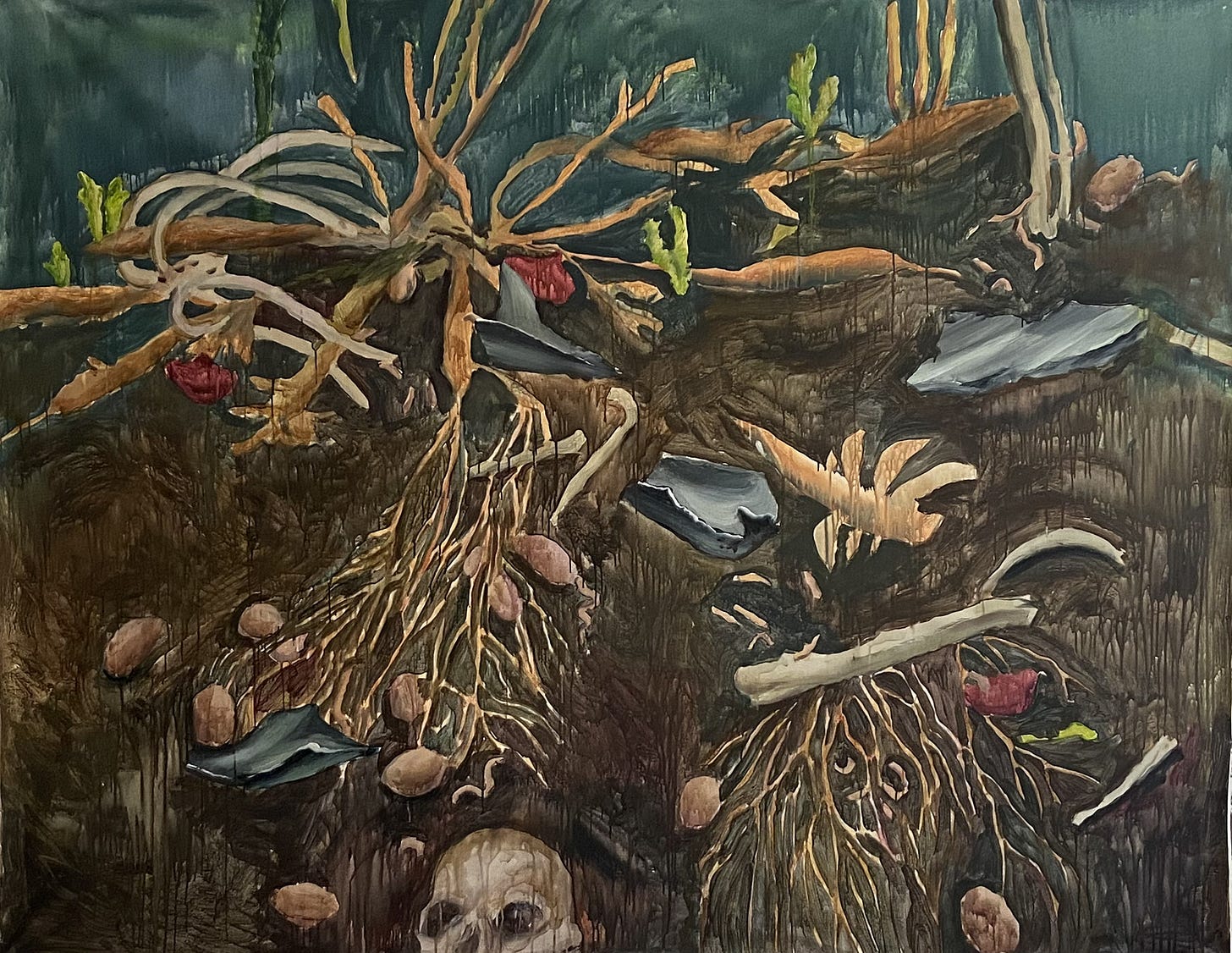

Kateryna Aliinyk

Kateryna Aliinyk is a Ukrainian artist and writer from my home city, Luhansk, the second-largest city of Donbas, the place where the Russian invasion started spreading in the spring of 2014 (along with the occupation of Crimea). The connection to her land spills all over Aliinyk’s canvases in a rich, earthy palette. What becomes more and more apparent in her painting are the striking effects the Russia-committed ecocide has on the inhabitants of the colonised territories. The land poisoned by war and Russian pillage of natural resources will take decades to recover, thus depriving the locals of food, natural shelter, and, of course, the landscape they know and love. The destruction of the land as a result of colonial war is rather underestimated, and Aliinyk’s artworks as a powerful testimony of this loss. For her, the familiar landscape means home, home means memory, and memory means self-identification.

Oleksiy Sai

“I work like a propagandist,” Oleksiy Sai says in one of his interviews. The series of posters he created does, in fact, contain brief and quick messages, sometimes written, sometimes expressed in visual markers. This one is yet another reflection on the role Russia gives to culture in its colonial ambition. The creature that resembles a two-headed eagle champions the heads of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, the Russian writers of the Imperial period, so hyped by the Western intellectuals. The crown is usually associated with the colonial force, but here, it is a bit crooked since Russian politics have been wavering between monarchy and socialism for a long time now. The creature is gifted with a pair of ballerina's legs (a reference to “exceptional” Russian ballet and Swan Lake) and floats gracefully in a grand jeté over a destroyed Ukrainian town. Spreading its tiny wings, the golden cultural mutant dances on the ruin it perpetuates.

Lesia Vasylchenko

Lesia Vasylchenko conducts profound and complex research on time. According to her essay Chronosphere, there are four dimensions of it:

the human dimension (the time one needs to get to the shelter during an air raid),

the natural one (the time needed for nature to heal after an ecocide war),

the data time (or Near-Real Time, needed for a signal to reach its destination, which revolutionised contemporary warfare),

the time we spend worrying about future disasters, which is the fourth dimension, the possible future that is not here yet.

In her video, Vasylchenko imagines a speculative Court of Time, which will gather to listen to the testimony of all non-human victims of the colonial war in Ukraine: the trees, the earth, the dust. Russia-committed ecocide in Ukraine is one of the persisting colonial weapons employed by Russia, and according to the artist, it is greater damage than any of us can imagine.

REMINDER: founding subscribers to my Substack and members of the highest tier on my Patreon have access to the Russian Colonialism 101 micro-website — the only live-updating database with the most relevant sources about Russian colonialism.

the empire will fall 🪆🪓

What a superb list - I saw Kadyrova’s piece in Lviv - and today I met the young artist Valentina Guk in Kharkiv. We were talking about the decolonisation of Ukrainian culture - including the Chervona Ruta festival which Valentina told me celebrated Ukrainian music in cities like Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv and Simferopol back in the 1990s, attracting tens of thousands of fans. I would love to hear more about it… Thank you so much for sharing all these wonderful resources!

Amazing and powerful art! Thank you for sharing! I also love the works of Ukrainian artist Olia Fedorova: https://www.oliafedorova.com/works/anger-exercises