russian colonialism 101: power imbalance.

i don't want russians to tell my story. it is about justice, not hate.

Russian Colonialism 101 is the first newsletter to shed light on Russian colonialism. The opening essay is public; the curated reading lists are behind the paywall. Your paid subscription will power my mission to mainstream awareness about Russian colonialism.

In my essays for the Russian Colonialism 101 Newsletter, I often focus on two vantage points: either how Russian colonialism works or why the rest of the world remains blind to it. This edition is going to be about the latter.

We’ve just had a couple of Berlin events premiering the Russian Colonialism 101 guidebook. I was overwhelmed by all the attention and curiosity. In both cases, the organizers had, at some point, shut the venue’s doors for crowd control. I am beyond grateful for everyone who showed up. And for those who didn’t manage to get in — I am already planning a Berlin re-do soon.

But right before this, I was approached by a reporter from one of the leading German news outlets. They saw the event’s promo and wanted to feature the book. I wasn’t familiar with the reporter, and so I did a basic background check first (a standard security practice for me.) They turned out to be a Russian. Most likely still a Russian citizen. I decided to ignore the request at first.

Why?

It is nothing personal. The reporter may be a stellar professional. But there are two ‘buts.’

First, we don’t talk enough about how Ukrainians get re-traumatized when forced into a shared space with Russians. There’s little awareness about the psychology of trauma for those who are surviving or have an intimate connection with an unfolding genocide. When fellow countrymen of that Russian reporter are hunting down my family members like animals, I don’t feel safe or comfortable simultaneously sitting down with them for a pleasant talk on smart topics. These feelings are beyond my powers. Is it fair to this one Russian person, even if they denounced the genocidal empire? Maybe not. But policing reactions of someone who is developing a trauma is not fair or humane either. Consider also layers upon layers of intergenerational trauma that we, as Ukrainians, have since this is not the first genocide Russians are committing against us. For example, a recent study on intergenerational transmission of genocide trauma in Rwanda suggests visceral resistance to reconciliation may last at least a generation or two after the abuse took place.

Second, there’s a multi-generational power imbalance. Taking into account centuries of Russians gate-keeping (and erasing) Ukrainian voices behind the Iron Curtain of Russian colonialism, I don’t want to reproduce the same cycle and trust another Russian to tell my story. A Ukrainian researcher of decoloniality, Mariam Naiem warns us in her latest brilliant essay that such chat simply cannot happen from a position of equals, disregarding personal backgrounds. Ukrainians communicating with the rest of the world have to pierce through not one but two types of colonial gaze. The first one is Russian colonial mythology. And second — the Western one that orientalizes both Russians (valorizing and mystifying the ‘perplexing Russian soul’) and Ukrainians (painting them as simpletons who come short of ‘Western standards’: difficult, messy, and guided by emotions.)

“At a time when one group is literally exterminating and conquering the other one, there is a palpable aura of impending danger in any interaction between the representatives of the two. This dynamic inevitably influences the tone and direction of the dialogue. Due to the archetypical view of anti-war Russians as complex characters, this hypothetical panel sets the conditions for the Russian to be perceived as complex, interesting, and likely rational, and the Ukrainian, whose family is likely split between being displaced and fighting a war, as emotional and biased,” Naiem writes.

But this is not the end of the story. Eventually, I changed my mind. And what happened next might tell you a lot about why many mainstream Western newsrooms remain blind to the phenomena of Russian colonialism.

I could have simply ignored the press request, right? Instead, I tried to contact the German newsroom management, which sent a Russian reporter to interview me. Not all Ukrainians have the luxury of negotiating safe and fair terms for mainstream foreign interviews — even people with large platforms like myself have to fight tooth and nail to get them. So, I wanted to ensure they knew and understood the reason why I was requesting a non-Russian reporter for the job.

My friends and I tracked down two prominent journalists from this newsroom. When contacted, the first one instantly acknowledged the problem and its validity. The second didn’t understand what I was talking about and suggested I first try to talk this out with the Russian reporter in question. Both are excellent journalists. However, the first one is a Western woman. The second one is a white Western man.

Why is the last aspect important to this story?

As a fellow journalist, I believe our lived experiences with injustice and disenfranchisement help us to recognize power imbalance in the stories we cover. It doesn’t mean someone from a privileged background cannot do it. But if the newsroom lacks diversity, this capacity would be next to zero.

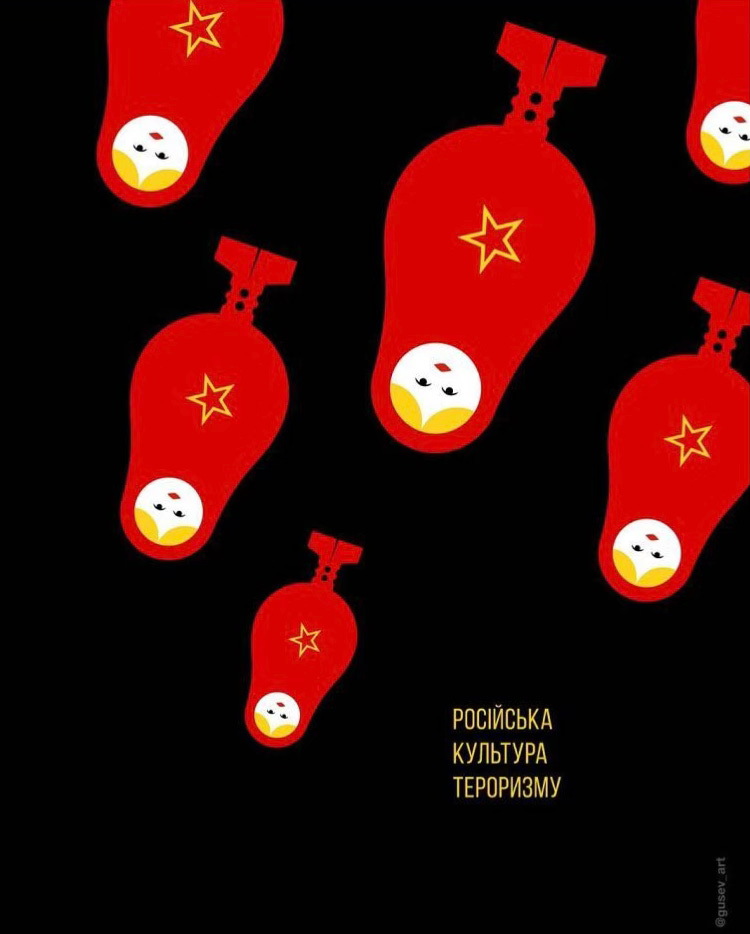

At the core, the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized is a relationship of abusive power imbalance. There are foreigners, especially those coming from privileged (imperial?) backgrounds, who struggle to ‘see’ it. But some see it and then try to ‘mediate’ it - which is even more problematic. A Ukrainian artist, Aliona Karavai recently wrote a moving essay addressing this paradox in the context of the European art world. But it has perfectly universal relevancy.

‘I find it intriguing how this self-appointment as a mediator happens,’ Karavai writes. ‘I wonder where this self-nomination comes from, despite the numerous voices from the Ukrainian community who, since at least 2022 (and some since 2014), have expressed the impossibility of artistic dialogue as long as rockets fly overhead. I question the expectations for explanations when Ukrainian female artists and curators reject proposals they never asked for. I express my confusion about whether these German institutions understand the multi-layered inequality between Ukrainian and Russian female artists created by the context of a genocidal war. Do they possess reliable tools and sufficient expertise to work adequately with such inequality, given that it will only deepen otherwise? And do they have the perspective even to recognize this inequality and its roots?’

The blindness to power imbalance or the unsolicited urge to mediate it — I have no idea which one drove the editors of that German newsroom to authorize a Russian reporter for my interview. But here’s the most ironic thing: both German colleagues promised to address the issue within the team and ensure someone else interviewed me. That was several weeks and 77,000 Navalny articles ago. Another colonial bias kicked in here, uniting Westerners regardless of their gender. But this one is not in the spotlight for this issue :)

here is what's in store for you this week:

Staggering parallels between the little-known history of Moscow starving hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians to death in the 1920s and today’s genocide;

The Russian invasion of Ukraine did not start in 2022. Or even in 2014. Russia has been trying to erase Ukraine since the 16th century. Without this vantage point, you can’t see the war in Ukraine for what it is: Europe’s latest anti-colonial war;

What about Russian colonialism during the Soviet era? We’ve got you covered with the story of the brutal re-colonization of the Sakha people in Northern Asia during the 20th century;

Learn more about the shared history of Polish, Lithuanian, and Belarusian struggle against Russian colonialism;

curious for more? let's go.