Russian Colonialism 101 is the first newsletter to shed light on Russian colonialism. The opening essay is public; the curated reading lists are behind a paywall. This newsletter is part of the Volya Hub network, which expands global awareness about Russian colonialism.

While on my first trip to Taiwan to present my Russian Colonialism 101 guidebook to the Taiwanese public and the Vice-President of Taiwan, I tried to remember my first memory about this defiant democracy.

A brawl. A violent fistfight on the parliament session floor. Angry and unruly Taiwanese MPs tossing each other around. That kind of imagery would usually be the only time when Taiwan was mentioned on the news while I was growing up in the 1990s Ukraine. Global newswires wouldn’t provide us with much of an alternative and Ukrainian newsrooms were too poor to send reporters there.

But with time I realized this one-dimensional coverage is not random and much closer to home than I originally thought.

After the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine when we defended our voting rights for the first time, democracy flourished. The real democratic competition raised political stakes, too. Empowered people became passionate about changing and shaping life in their own country. And yes, that passion would often come with brawls on the parliament session floor. No worse or less spectacular than the Taiwanese. I was eager to explain to the world the complexity and vibrancy behind the facade of parliamentary fistfights.

Oh boy, was I naïve.

Foreign Western editors were only interested in entertaining footage of the fights, not the context. This one-dimensional perspective spread like cancer in years to follow. With time, Ukrainian democracy was mostly presented as messy, dysfunctional, and unruly. Uncivilized. Global coverage of Taiwan would often carry the same vibe. Without maybe even realizing it, global legacy newsrooms were looking at us with an imperial gaze.

It was not a coincidence that both Taiwanese and Ukrainian democracies exist next to imperialistic tyrannies: Russia and mainland China. Both have existential fears of allowing the spirit of freedom, diversity, and dignity to flourish over the border and serve as inspiration for their imperial subjects. Both spend billions to spin the imperial propaganda that they are the fortresses of order, stability, and civilization. And that we are simply mad for refusing this gift of civilization.

In my Russia Colonialism 101 guidebook, I pay extra attention to how the Russian empire has historically been using gaslighting as part of its invasion toolkit. Presenting your victim as mentally unstable and in need of ‘saving and curing’ is integral to Russian imperial conquests.

So it is less abstract and more closer to home, let me share a few examples.

Just several months ago some of my family members escaped the Russian occupation after the colonial authorities threatened to steal their newborn baby. The reason? Because the parents did not get a Russian passport and therefore ‘mentally unfit to be parents.’ It is not a freak case. With at least 19,000 Ukrainian kids stolen by Russians in the last two years of genocide in Ukraine, alone, many reportedly were taken away from ‘unfit’ parents. Being an unapologetic Ukrainian or indigenous self is a mental illness in the eyes of the Russian empire. Has always been.

‘It’s important for us to understand how Russian imperialism differs from Western imperialism, which colonized distant ethnic, racial, cultural, and linguistic profiles. In such an empire, the instrument of domination is the notion of difference: you are different from me, and you will never become like me,’ says a prominent Ukrainian philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko. ‘Russian imperialism (at least in relation to Ukraine - ed.) is different. When it colonizes Ukrainian, it says: you will never be different, you will only be like me. Your chance to survive is to assimilate, to become like me. Anything different is a deviation, a mental, psychological, cultural aberration.’

During the second half of the 20th century, institutionalizing freedom fighters, dissidents, and anti-colonial thinkers as “clinically insane” became a routine for Moscow. The Russian empire of the Soviet stage used a tight ideological grip on sciences to harness and weaponize entire psychiatry in the fight against anti-imperial dissent. For example, back in the 1970s, Russian occupation authorities arrested a prominent Ukrainian human rights defender and journalist Leonid Plyushch, and put him into a KGB-run psychiatric ward. What was his crime? ‘Mad ramblings’ like these:

“When I decided to start speaking my native Ukrainian language in public, it was tough at first. My vocabulary was poor and everyone around me would keep using Russian. But that one time I asked a young person in Ukrainian to pass me a book. He snapped: ‘Can you speak like a human, maybe?’ (a popular colonial micro-aggression, mostly by Russians or Russified people, suggesting that the Russian language is the language of civilized humans vs barbarian ‘animalistic’ indigenous languages - ed.) Blood rushed to my head. That was the moment I finally became fully Ukrainian.”

The effects of this entrenched culture of pathologizing your desire to be free are lingering and intergenerational. Last year my Lithuanian friends produced a brilliant documentary for The Changemakers streaming show, that traces bizarrely high suicide rates in the country to a severe lack of trust towards mental health professionals after decades of Russian colonial occupation.

This gaslighting left a deep mark on our cultures, too. For one, the ideas of insanity and the desire for social justice are tightly interlinked in the canon of Ukrainian literature.

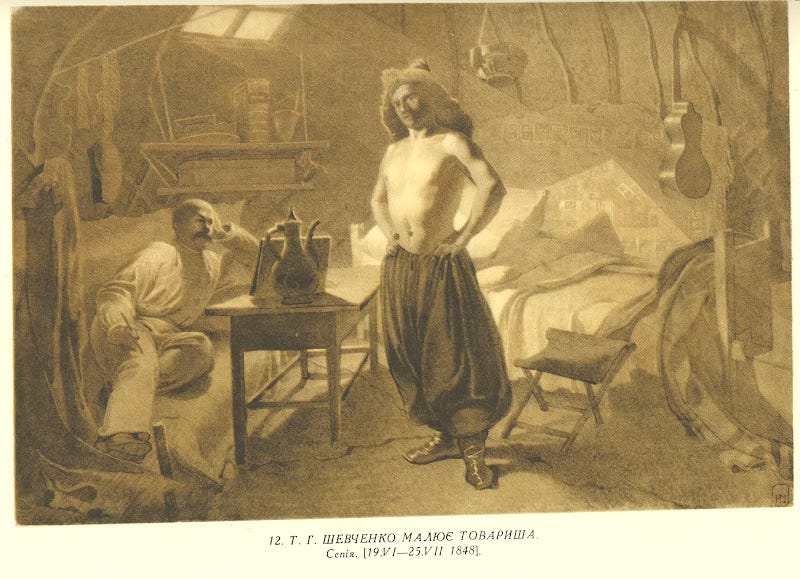

In his trailblazing work on the anti-colonial roots of Jewish-Ukrainian literature ‘The Anti-Imperial Choice,’ (I am featuring it in this edition’s must-reads down behind the paywall) Ukrainian-American writer Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern juxtaposes the most prominent works of Ukrainian writers of the 19th century, Taras Shevchenko and Hryts’ko Kernerenko, along the same line. For example, Shevchenko’s ‘Sova’ (1844) is about a mother traveling across the Russian empire in futile attempts to find her Ukrainian conscripted son, she turns insane in response to imperial indifference to the fate of a suffering individual; or ‘Maryna’ (1848) is about a Ukrainian woman experiencing a mad rage outburst following a slavery abuse. And one of Kernerenko’s most prominent works is ‘Pravdyva Kazka’ where a Ukrainian woman is trying to stop a Jewish pogrom and turns insane from her failure to prevent injustice.

In the eyes of the empire, seeking justice and resisting colonial assimilation is a mental illness. Generations of Ukrainian artists centered this idea in their works.

Whether foreign media coverage or Western academic halls, this gaslighting has also infiltrated the way indigenous expertise is universally considered by Western academic elites as ‘emotional.’ As a prominent scholar of Ukraine, Rory Finnin reminded us recently: ‘Pitting emotion against reason -- is a false polarity too often caught up in gendered stereotypes. But there is no thought without feeling, and no feeling without thought -- as philosophers from Bergson to Nussbaum make clear… Being close to and active in a country defending itself in a genocidal war is an analytical asset, not a liability. Being present to and expressive of emotions as people suffer is a sign of an intellect attuned to brutal reality.”

I am struggling to finish this essay because it happened so the day Russians bombed the kids’ cancer hospital in Kyiv. A wave of gaslighting arrives almost simultaneously with these heinous crimes. Are you sure it was a Russian missile? Are you sure the target was the cancer hospital? Are we sure emotional Ukrainian claims should be trusted? It is maddening and makes you start questioning yourself. But the design of this gaslighting is not random, though. A confusion tactic, it keeps us all from asking the most important questions:

are we living in a world where such war crimes can happen without accountability and justice served?

and if yes, does it mean that our system of international law has fully collapsed?

and if yes, are we prepared for the bleak and exceptionally violent dark ages ahead?

These kinds of questions that modern-day tyrants of imperialism do not want us to raise. The more you are confused and the more emotional the victim is presented, the less you are inclined to act. Ukrainian philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko warns against the grave consequences of such inaction:

‘Will the 21st century be a century of the restoration of big empires? Today we are witnessing the resurgence of imperialism everywhere: not only in Russia, but also in China, Türkiye, India. In this context, our role is very important for the world, because we are essentially standing on the brink of this wave of new imperialism. If we do not stand firm, imperialism will spread further. And we will find ourselves in a situation akin to 1939, once again.’

Demanding justice is not crazy. Remember that.

I’ll leave you with a translation of this verse by a Ukrainian anti-colonial legend and writer Lina Kostenko:

One must possess a satanic aim,

And harbor it within an incurable rabies,

To torment us with cruelty so vast,

And then accuse us for all that has passed!

REMINDER: founding subscribers to my Substack and members of the highest tier on my Patreon have access to the Russian Colonialism 101 micro-website — the only live-updating database with the most relevant sources about Russian colonialism.

here is what's in store for you this week:

how being a Jewish-Ukrainian has always been a powerful act of anti-imperial resistance driving the Russian empire mad;

why do most Russians support genociding Ukrainians and what does it have to do with the deeply-rooted Russian culture of imperialism;

Finnish Bucha that you have most likely never heard about;

why it is important to recognize Stalin’s genocides;

The ‘Dune’ and Russian colonialism connection that you had no idea exists;

how extremist anti-environmentalism has been integral to the Russian colonization of southern Ukraine.

curious for more? let's go.